A Brief Overview of Storytelling in the Middle Ages and Renaissance

Everyone is a storyteller. Anyone who says otherwise is telling you a story

– Master Owen Alun

Storytelling, an age-old art form, has played a crucial role in human societies, shaping cultures, traditions, and historical discourses. The medieval and renaissance periods were eras of immense storytelling development and innovation, resulting in a rich tapestry of narratives that continue to influence contemporary art and literature.

In the medieval period (5th to 15th centuries), storytelling was primarily an oral tradition. From the epic sagas of the Norsemen to the moral parables of religious texts, stories were a key mode of communication and education. Tales were often told through poetry or song for years, sometimes centuries before being transcribed. Notable works include the Arthurian legends, Beowulf, and the Chanson de Roland, reflecting themes such as heroism, divine intervention, and societal expectations.

The renaissance period (14th to 17th centuries) witnessed a shift from predominantly oral storytelling to the written form, powered by the invention of the printing press. Literature flourished with a renewed interest in humanism, exploration, and scientific discovery. This period birthed the novel, short story, and essay, genres that allowed for more personal, introspective storytelling. Writers like William Shakespeare and Dante Alighieri authored some of the greatest works of storytelling ever produced.

Both periods greatly emphasized allegory and symbolism, with stories often having deeper, underlying meanings. The narratives were enriched with archetypal characters, vivid descriptions, and intricate plotlines, aiming to provoke thought and evoke emotional responses from the audience. These stories were not just simple tales; they were vehicles to convey moral lessons, comment on societal norms, and speculate on the nature of the universe and humanity’s place within it.

Casual Storytelling vs. Theatrical Storytelling

The ideal level of interplay between storytelling, acting and theatricality must always depend on the context of the telling: it will be particular to the teller, the tales that s/he is telling, the nature of the audience, and the time and place of the performance.

– Alastair K. Daniel, Storytelling Performance Part 1

When it comes to conveying a narrative, casual and theatrical storytelling represent two contrasting styles. Each offers a unique way to engage with stories, and understanding the nuances of each can enrich not only our appreciation of the art of storytelling, but our ability to give an engaging performance.

Casual storytelling typically occurs in daily life amongst friends, family, or co-workers. It’s an informal and often spontaneous exchange that can cover personal experiences, interesting anecdotes, shared events, or even dream recounts. The aim is less about performing and more about sharing and establishing a connection. This kind of storytelling doesn’t usually follow a strict narrative structure and can include lively back-and-forth exchanges, interruptions, and detours.

In contrast, theatrical storytelling is a more formal and structured narrative method. Generally carried out in front of an audience, and may include elements of drama such as costumes, and props. The story is carefully planned and practiced, with a clear start, middle, and conclusion. Also, theatrical storytelling techniques, like monologues, dialogues, and dramatic pauses are employed to add richness and depth to the narrative.

Storytelling Structure and Plot

A story is the telling of an event, either true or fictional, in such a way that the listener experiences or learns something just by the fact that he heard the story. A story is a means of transferring information, experience, attitude or point of view. Every story has a teller and a listener.

– Mark W. Travis, What is a Story and Where Does It Come From?

A story is a narrative or account of a series of events, real or imaginary, presented in a sequence. It involves characters undergoing experiences or facing situations, and it follows a structure that includes a beginning (introduction), middle (development), and end (resolution). But what does that mean?

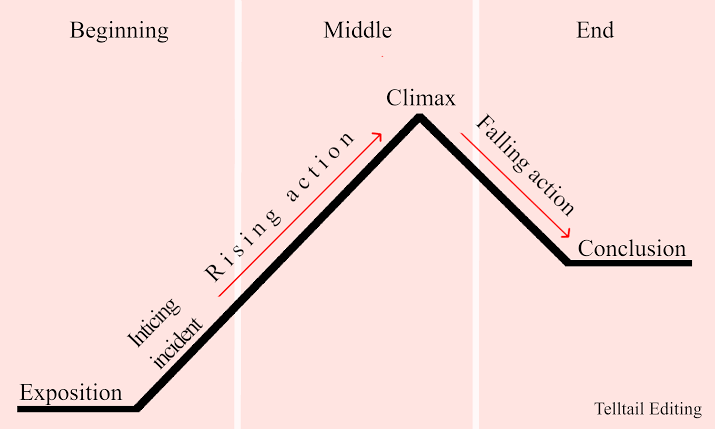

This is Freytag’s Pyramid, a model of dramatic structure for storytelling and narrative analysis. It maps out the common patterns of plot elements in a five-act structure, though it can also be applied to narratives with different numbers of acts. The five key stages in Freytag’s Pyramid are:

- Exposition: This is the introductory part of the story, where the setting, characters, and basic situation are established. The background information necessary for understanding the rest of the story is provided here.

- Rising Action: Following the exposition, the story enters a phase where the main characters face a series of conflicts or challenges that build tension or suspense. This is generally where the plot thickens, and complications arise.

- Climax: This is the turning point or the most intense moment of the story, where the main conflict or problem reaches its peak. The outcome of the story usually hinges on the events at the climax.

- Falling Action: After the climax, the story starts winding down. The pace may slow, the tension reduces, and the story moves towards its conclusion. The events during this phase lead towards the resolution of the conflicts or problems.

- Resolution: This is the final part of the story, where all loose ends are tied up, conflicts are resolved, and the story concludes. The resolution may contain a final moment of suspense or surprise, but ultimately it aims to bring the story to a satisfying end.

As you can see from the illustration, story structure and plot are intrinsically linked. They work together to shape and guide the narrative of the story from start to finish.

Plot refers to the sequence of events or actions that occur in a story. It’s what happens in the story – the actions, conflicts, and resolutions that the characters experience. Story structure, on the other hand, is the framework or model that organizes these events in a specific order to create a cohesive narrative. It determines when and how these plot points are revealed, and it provides the pacing and rhythm of the story. Essentially, it’s the blueprint for the story, outlining when key events should occur to maximize tension, emotional impact, and the audience’s engagement.

Performance Fundamentals for Storytelling

You want to ask yourself,” What is my purpose when I’m telling this story?

– HL Maire nic Siobhan, Dream Weaving; Storytelling in the SCA

While story is at the center of all of the bardic arts, it can take effort to master the art of pure storytelling, especially for the modern audience. For example, when I perform a song I have three tools to use.

- Lyric – The lyric carries the rational narrative, the who, what, where, and when.

- Melody – The melody carries the emotional weight, happy, sad, romantic, etc.

- Music – The music sets the mood and pacing, energetic, martial, whimsical.

As a storyteller you have to leverage the spoken word to convey all of that. This is where understanding the difference between casual and theatrical storytelling comes into play. Telling your friends a story about your day on the field is not the same as performing a story at the bardic circle. How, exactly, do you perform a story?

- Move Toward Theatrical Storytelling

You don’t have to have props, stand-up, exaggerated gestures, or use different voices to tell a good story, but that doesn’t mean you’re not allowed to have and do those things. Expand your possibilities. Include gestures, a trinket, a puppet or some other prop. If you decide to do any of those things make sure to practice and rehearse them. - Understand the Structure of The Story

Remember Freytag’s Pyramid, and look closely at how events are laid out. There is a beginning, a middle, and an end. Each part contains certain elements. This is not accidental. Over the years a number of books have been written about narrative structure, with many scholars, academics, and authors analyzing countless stories and developing various theories to describe how they work, but the principles in Freytag’s Pyramid are remain largely unchanged. - Know on the Plot Points

Over the course of any story there are major events, and there are minor ones. Don’t focus on the minor one, don’t try to memorize them word for word. Instead, because you understand the narrative structure, you can paraphrase, or even improvise, these intermediate passages.

Don’t try to memorize the whole story word for word because if you lose a word, and you will, you’ll be lost. Know the story, beginning, plot point, plot point, end, and fill in as you go because it will come out better and you won’t be lost if you lose half a sentence.

– Mistress Morgana bro Morganwg

- Avoid Introductions and Explanations at the Beginning

Your goal here is to tell the story, not tell your audience about the story. Remember the narrative structure and the parts that fall within the Exposition, that’s where you give them this information. - Slow Down

Talking too fast is a common problem that stems from anxiety. The best way to address that anxiety, regardless of its cause, is to make sure you are well rehearsed. - Shorter is Better Than Longer

The longer the story (or the song, poem, ect.), the more restless audiences generally become. Try to avoid anything longer than five minutes. As your skill in the art of storytelling increases so will your renown, and with it opportunities to perform longer pieces in front of an audience that’s there just to hear you. - Keep it Simple

Don’t get bogged down in minor details, instead try to keep it moving at a steady pace from plot point to plot point. Often in the course of a story we don’t kneed to know why Oden’s horse has eight lags, only that it has eight legs. - Be Aware of Your Own Performance

This is where the amount of rehearsal you’ve done really comes into play. The better you know your material the easier it will be to maintain awareness of what you are doing in the moment, how your performance is being received by the audience, and what changes you might want to make. - Be Considerate of Your Audience

Remember that your audience is composed of many people, all with their own reason for being there. Some came for a good story, some for mild family entertainment, and some are there to perform themselves. Be sure to ask yourself if the piece you’re considering is going to be well suited to the audience you’re performing for.

Final Thoughts

As I said above, storytelling is perhaps the most difficult bardic art to master. I think that part of this is that storytelling, in all it’s many facets, is so common in our everyday lives. Much like the other skills we have learned by being immersed in our culture they don’t look hard because we’ve never really had to try to learn them. For most of the stories we tell from day to day a casual style is not only easier, but more appropriate.

Performing a story requires a greater of investment of time and effort. You need to find and evaluate material, consider your ability to perform the piece, the places where it may be well received, and the places it won’t. After that you’ll need to devote time to practice and rehearsal. Only after all that work has been done will you be ready to give a good performance.

References

Throughout the writing of this document I have relied on many sources. Because this document is focused on performance, and not any of the other topics that naturally arise from the art of storytelling, I have had to leave out much of what I learned. I encourage you to look at these sites to learn more about storytelling.

- The Story Tent

- What Is a Story, and Where Does It Come From

- Dream Weaving; Storytelling in the SCA

- Questions for Storytelling Performance

- What is Storytelling?

- Your ultimate guide on how to be a good storyteller

- Capturing the Art of Storytelling: Techniques & Tips

- Pixar in a Box – The art of storytelling